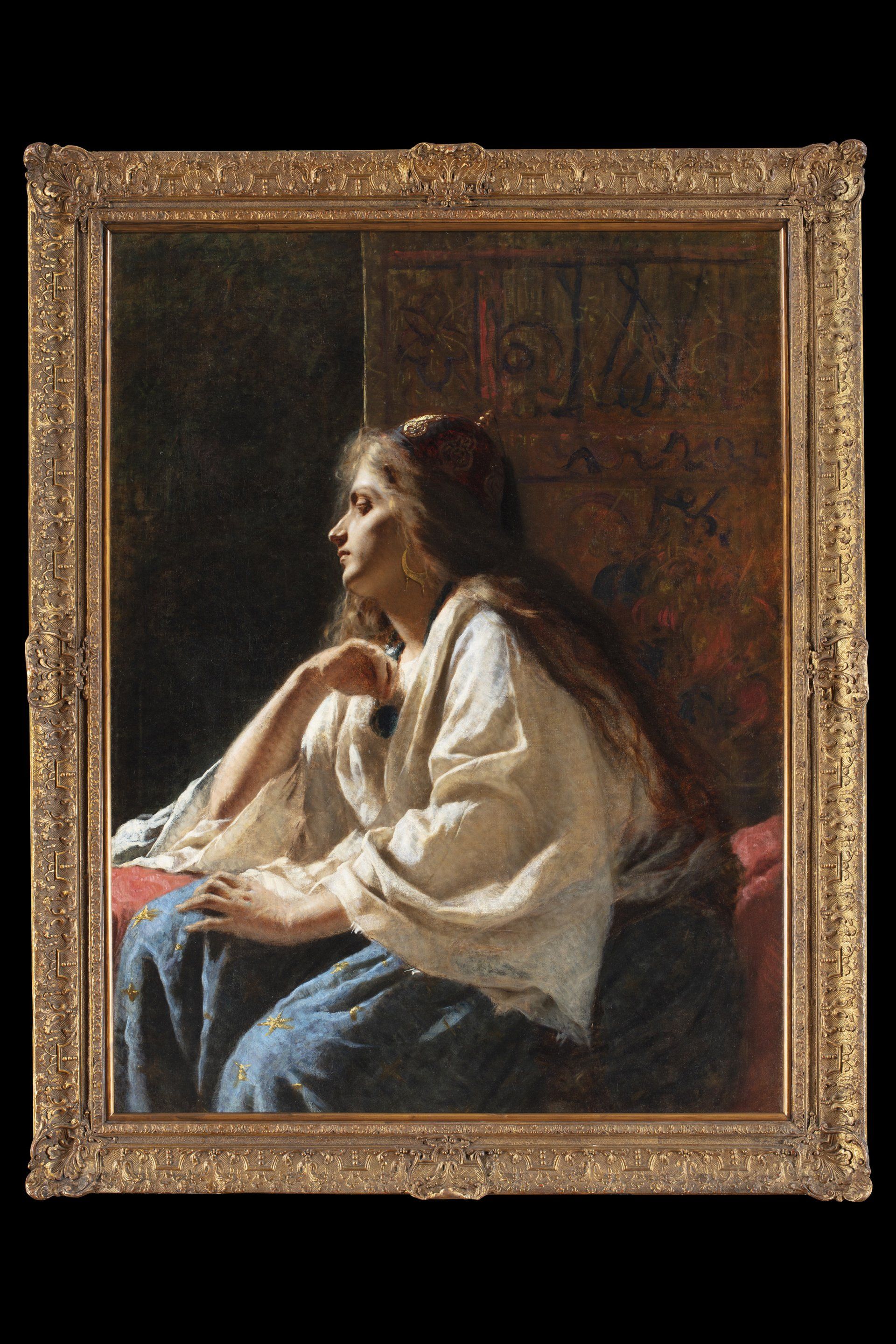

CESARE SACCAGGI

CESARE SACCAGGI

(Tortona 1868 - 1934)

To Babylon (or Semiramis)

About 1905

oil on canvas with gold and colored stones, 240 x 140 cm

signed lower right: Saccaggi

Provenance:

private collection, Turin

Exhibitions:

1993, Turin, Lingotto Fiere, Biennial of Antiques "Ancient Art"; 1998-1999, Stupinigi (Turin), Palazzina di Caccia, The Italian Orientalists. One Hundred Years of Exoticism 1830-1940, n. 107; 2008, Tortona, Guidobono Palace, Cesare Saccaggi. Between Eros and Pan, n. 44

Bibliography:

A. Dragone, in the nineteenth century. Chronicles of the Italian Art of the Nineteenth Century, n. 18, Milan 1989, p. 279, pl. III; F. Desk pad, Cesare Saccaggi. Notes for a biography, in Cesare Saccaggi 1868-1934, edited by M. Galli and F. Sottomano, catalog of the exhibition (Canelli, Galleria “La Finestrella”, 7-31 December 1996), Santo Stefano Belbo 1996, pnn; P. Lodola, in The Italian Orientalists. One Hundred Years of Exoticism 1830-1940, edited by R. Bossaglia, exhibition catalog (Stupinigi, Palazzina di Caccia, 13 September 1988 - 6 January 1999), Venice 1998, pp. 81, 203, 209; Cesare Saccaggi. A multifaceted "international" painter 1868-1940, edited by V. Basiglio, R. Billotta, M. Ferretti, Tortona 2000, pp. 17-18, 26, 78-79, 92, 99; P. Dragone, 19th century painters in Piedmont. Figurative art and culture 1865-1895, Genoa 2003, p. 362; L. Giachero, in Cesare Saccaggi. Tra Eros e Pan, edited by M. Galli, M. Bonadeo and L. Giachero, exhibition catalog (Tortona, Palazzo Guidobono, 13 December 2008 - 8 March 2009), Turin 2008, n. 44, pp. 171-172.

“Nature has given me a woman's body, but my actions have made me equal to the most valiant men. I held up the empire of Nino which goes east to the river Inamene, south to the land of frankincense and myrrh, north to Scythia and Sogdiana. Before me no Assyrian had ever seen the sea, I have seen four, which no one had ever reached because they were too far away. I forced the rivers to flow where I wanted and I channeled them to places where they were useful: I fertilized the barren land by irrigating it with their waters. I have erected impregnable fortresses, I have pierced impassable mountains with picks to make roads. I have procured roads for my chariots, where not even wild beasts had ever advanced. And in the midst of all these occupations, I found time for my pleasures and loves ”.

(Polieno, Stratagemata, quoted in G. Giorello, Lussuria. The passion of knowledge, Bologna 2010, p. 67)

The myth of Semiramis has its roots in late antiquity. Historiography, religion, art and literature have contributed to passing on different and contradictory legends linked to her figure over the centuries: some recognize her as the enlightened Assyrian ruler Shammuramat - wife of King Shamshi-Adad V and regent of his son Addu-Nirari III -, to whom we owe the realization of the hanging gardens of Babylon; for others Semiramis is the daughter of a nymph, abandoned in the desert and then fed by doves - the 'daughter of the air', according to Calderón de la Barca and Carlo Gozzi -; for still others she is the daughter of the goddess Derceto and the Syrian Caistro, married first to Onne, then to King Nino, with whom she had a son who, according to tradition, when he became an adult, chased her from the throne and killed her. During his reign, Semiramis conquered Mesopotamia, Egypt and Ethiopia. Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus speak of her as a great and good sovereign: the second does not attribute to her the idea of the hanging gardens of Babylon but the construction of other buildings, including the seven walls of Ecbatana. In the Middle Ages, according to the text of Paolo Orosio [i], Semiramide is counted among the most licentious of the powerful, alongside Cleopatra and Zenobia of Palmyra. Pagan symbol of incestuous love, Dante places it in the second circle of Hell, populated by the lustful.

This narrative richness has fascinated numerous opera and theater librettists over the centuries: in the eighteenth century, in particular, a large number of texts circulate, from Francesco Silvani to Pietro Metastasio, from Giacomo Meyerbeer to Gioacchino Rossini. The literary source of all these works is Voltaire's tragedy Sémiramis, performed for the first time at the Comédie Française in Paris on 29 August 1748 and disseminated in Italian in the 1772 translation by Melchiorre Cesarotti. the figure of Semiramide begins to be re-evaluated on an artistic level. In 1860 Degas portrayed her in ancient clothes as she admired the construction works of the city of Babylon (Paris, Musée d'Orsay). The theme, with its intertwining of lust and blood, is then taken up more frequently by artists linked to the climate of decadence. This is the case, for example, of Cesare Saccaggi in whose works he tries to revive the timeless world of myth, who at the end of the nineteenth century rediscovers the lost Olympus in the lands of Europe. The fallen gods thus return to tell their loves, the heroes relive their deeds, men accompany with songs the rebirth of a dreamed and reassuring Golden Age. However, the charm of Saccaggi's art also lies in his ability to lead - as if by magic - to a place where the enchanted senses, transhumanized in their fullness, have created a world of incorruptible and harmonious figures, which also have roots in its most profound physiological experience. But it is a world without cracks, without communication with the outside, outside those dark and secret roots. The mythical characters of Saccaggi are not the calm and narrative ones of the ancient; on the contrary, they are the myths of a modern artist, born from a restless and complex inspiration, at times even obscure. In this poetic, ardent and finished world, our reality does not even enter as a presentiment or memory, it is simply ignored.

This is evident in the stupendous A Babilonia of 1905, where archaeological and theatrical suggestions coexist in perfect symbiosis with those of the elegant society of the time and its most eccentric protagonists, such as the 'divine' Marquise Casati, who, like this Semiramide, was usual to show up in public with a leopard on a leash. The readiness to sensory stimuli arising from the figure - all voluptuous - of the Babylonian queen leads here to the manifest manifestation of amorous pleasure; a deeply sensual pleasure, which reverberates in the surrounding environment dominated by the colossal simulacrum of the winged bull, identical to the neo-Assyrian one from the Palace of Sargon II in Korsabad, admired by Saccaggi at the Louvre during his stay in Paris (1900-1905). The artist presents her to us as a young woman - deliquescent in her musical substance - suspended in a joy of living, in a feeling of absolute carnal pleasure that runs through and imbues things: her eyes sparkle, the outlines evaporate in the dark atmosphere of bottom: a 'non-place' where time has suddenly stopped. The woman does not look at us, her attitude suggests a detachment from the outside world, to the point that any contact with her, with her gaze, her thoughts, her story is impossible. The dress she wears, with a secessionist taste, so luminous, so admirably light and transparent, broken down just enough to allow a glimpse of the underlying nakedness, also contributes to the charm of the picture as much as the pale complexion of the face, which clearly detaches from the background, thanks also to the particular headdress that the queen sports with icy elegance [ii]. Saccaggi plays with colors, volumes, tops, in a kind of improvisation, bordering on virtuosity without losing the nobility and seriousness of the technique.

As repeatedly highlighted by the critics [iii], the iconographic and stylistic precedent of A Babilonia is the Judith painted by Gustave Klimt in 1901 [iv], especially for the particular association of death and sensuality, of Eros and Thanatos, which so fascinates the Central European culture of the early twentieth century. But it is above all from the context of Art Nouveau and the esoteric art of the Rose Croix that Saccaggi draws to give the painting an emotional charge that is sublimated into an image of rare intensity. His sensitivity even leads him to insert stones and gold foils on the pictorial surface. A choice also inspired by the graphic work of Alphonse Mucha, and in particular by the study for Salammbò [v], from which the Tortona artist draws inspiration to design the compositional system and the exotic formal declinations.

An art, that of Saccaggi, which wants to please and excite through the eyes; an art in which the painter recognizes the reasons for his most authentic and genuine poetics, and where the joy of creation is visible, impetuous and vigorous, animating colors and shapes.

Stefano Bosi

[i] Historian of the V century. AD, Paul Orosio tells how Semiramis legitimized his dishonest conduct, making legal what each of his subjects liked.

[ii] The headdress has on the sides two sumptuous earphones of Iberian derivation, probably inspired by those that adorn the head of the famous Lady of Elchè (Paris, Louvre).

[iii] See: P. Lodola, in Gli orientalisti italiani. One Hundred Years of Exoticism 1830-1940, edited by R. Bossaglia, exhibition catalog, Venice 1998, p. 209; L. Giachero, in Cesare Saccaggi. Between Eros and Pan, edited by M. Galli, M. Bonadeo and L. Giachero, exhibition catalog, Turin 2008, no. 44, pp. 171-172.

[iv] The work is kept in Vienna at Österreichische Galerie Belvedere.

[v] The work was published in lithography in May 1897 in the magazine “L'Estampe Moderne” together with the homonymous novel by Gustave Flaubert set in ancient Carthage.

___________________

[1] Historian of the V century. AD, Paul Orosio tells how Semiramis legitimized his dishonest conduct, making legal what each of his subjects liked.

[1] The headdress has on the sides two sumptuous earphones of Iberian derivation, probably inspired by those that adorn the head of the famous Lady of Elchè (Paris, Louvre).

[1] See: P. Lodola, in Gli orientalisti italiani. One Hundred Years of Exoticism 1830-1940, edited by R. Bossaglia, exhibition catalog, Venice 1998, p. 209; L. Giachero, in Cesare Saccaggi. Between Eros and Pan, edited by M. Galli, M. Bonadeo and L. Giachero, exhibition catalog, Turin 2008, no. 44, pp. 171-172.

[1] The work is kept in Vienna at Österreichische Galerie Belvedere.

[1] The work was published in lithography in May 1897 in the magazine “L'Estampe Moderne” together with the homonymous novel by Gustave Flaubert set in ancient Carthage.

Related works

View more

Share on your social profile

Contact us for information regarding the work on display

Fill out the form or call to arrange a meeting Mobile 39 335 8125486 Mobile 39 335 7774612

Opening time

- Monday

- - -

- Tue, Wed, Fri

- - -

- Thursday

- -

- Saturday

- - -

- Sunday

- Closed

Via Roma, 22 / a, 42100 Reggio Emilia RE

contact info

Ph. 39 0522 704575

Mobile 39 335 8125486Mobile 39 335 7774612

Follow us also on social networks

Sign up to our newsletter

and stay informed